Share This Article

Without binding rules, the threat of space debris grows – and so does the risk of global disruption.

High above us, millions of fragments of old satellites and rocket parts race around the planet at 15 times the speed of a bullet. Yet no one is responsible for cleaning them up. A single collision in orbit could spark a global crisis in a world that relies heavily on satellites – GPS, banking, weather, and even warfare. But space legislation has left a void, offering no clear rules. For Dimitra Stefoudi, an assistant professor for space law at Leiden University: “Debris is the number one issue because, according to calculations, it’s a disaster waiting to happen.”

The Hidden Threat Orbiting Above

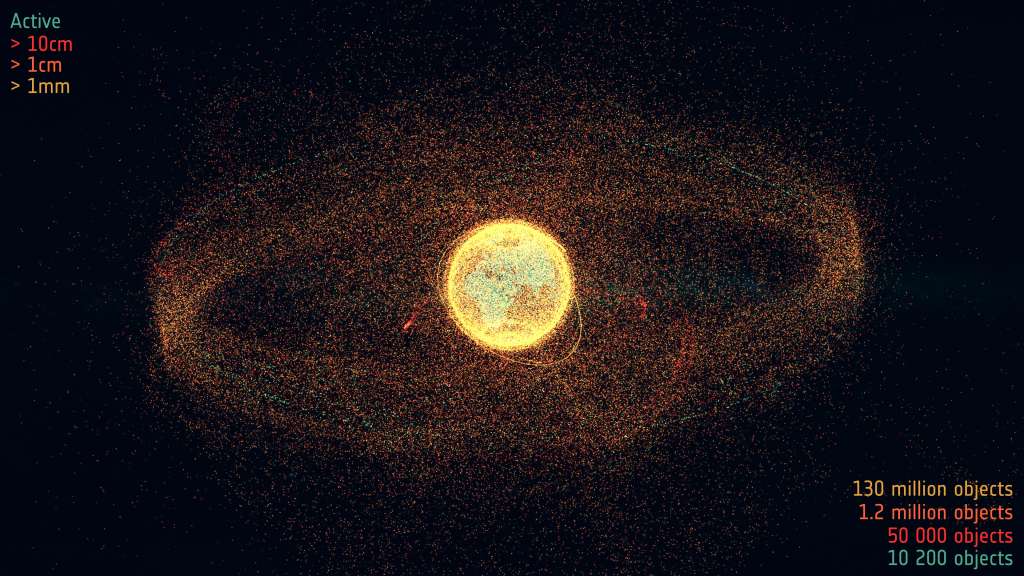

“Space debris” refers to man-made objects in orbit that no longer serve a purpose – from defunct satellites to fragments from past space missions. These objects often remain in orbit for decades. The European Space Agency (ESA) estimates that over 26.000 pieces of debris larger than 10 centimeters are orbiting Earth, and more than 1 million fragments exceed 1 centimeter. Tiny, yes – but their speed of up to 15 kilometers per second makes collisions with spacecraft potentially catastrophic and deadly for crew members.

The problem is accelerating. Companies like SpaceX have made rocket launches more affordable, and a greater number of objects are being launched into space than ever before. Ten times as many new objects were launched into orbit in 2024 as in 2013. Today, over 14.700 active and inactive objects orbit Earth. In low Earth orbit, up to 2.000 kilometers above ground, thousands of Starlink satellites crowd the skies, further congesting an already busy region.

The Risk of a Chain Reaction

While these constellations bring the internet to the most remote regions on Earth, they also heighten the risk of collisions. As debris accumulates, the risk of a cascade effect – known as the Kessler effect – increases. First described by Don Kessler in 1978, it refers to a chain reaction where collisions generate more fragments, exponentially increasing the likelihood of further collisions. A single collision could trigger widespread damage in a short time. The risk is not limited to academia: in 2009, an active US satellite collided with a defunct Russian satellite, creating about 1.800 fragments larger than 10 cm and countless smaller pieces.

The consequences could be severe. Essential services like GPS navigation, weather forecasting, and telecommunications could fail. Everyday activities – from emergency responses and air travel to internet access and financial transactions – would suffer immediate disruption. Even minor inconveniences could ripple through daily life: imagine getting lost without Google Maps or not being able to fly to your mom’s birthday.

Outdated Laws in a Crowded Sky

Despite the mounting risks, the legal framework remains limited. There is no universally accepted legal definition of “space debris,” and no binding international agreements specifically focus on its removal. Although two treaties outline liability for damage caused by spacecraft or debris, neither treaty mandates active debris removal or preventive measures.

Still, the threat of liability provides some incentive for caution. “It does prompt countries or companies to explore whether something will be potentially harmful,” says Stefoudi. “If nothing else concerns you, knowing that something you launch – when it’s turned to debris – may cause damage, and you will be liable for that damage – is incentive enough to take it seriously.” Without binding cleanup obligations, liability serves as an indirect check on debris creation.

Stefoudi emphasizes that debris mitigation must evolve alongside technological advancements, and that the need for global regulation may not be the best way: “Debris, for example, is an area that, technologically speaking, I’m not sure having an international framework will help because whatever is mitigating debris now may not be mitigating debris tomorrow.”

Too Slow for Progress

New laws are unlikely anytime soon. The United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UN COPUOS) operates by consensus, requiring all 102 member states to agree before proposals can move toward a treaty or resolution—a high hurdle.

Nonetheless, the issue of space debris is not ignored. In 1993, the European Space Agency (ESA) helped establish the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC), which is composed of space agencies rather than states. The IADC adopted the Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines in 2002, which were later updated and endorsed by the UN General Assembly in 2007. Though non-binding, these guidelines recommend best practices such as designing spacecraft for controlled reentry, preventing collisions, and safely disposing of defunct satellites.

In practice, some guidelines have become de facto rules. Stefoudi explains: Debris guidelines that are by definition not binding have become binding because they are becoming, in many countries, licensing requirements.” Modern spacecraft must meet strict standards to receive operating licenses.

A Race to Clean Up Space

Beyond mitigation, active debris removal is gaining momentum. In February 2024, Japan launched the ADRAS-J mission, which successfully approached a defunct rocket body within 15 meters and captured detailed images to assess its condition. The mission aims to develop techniques for safely deorbiting such debris. NASA and ESA are pursuing similar projects. ESA has contracted the Swiss company ClearSpace for a €68 million mission planned for 2029. The ClearSpace-1 mission intends to approach, capture, and deorbit a piece of space debris, bringing it into Earth’s atmosphere to burn upon reentry.

Space Debris is Like Climate Change

But time is ticking. SpaceX alone plans to deploy over 12,000 satellites in low Earth orbit. Especially for emerging countries, which rely heavily on affordable satellite technology in this orbit, the consequences of a debris disaster could be devastating. Sending new satellites into space remains cheaper and faster than cleaning up existing debris, making the risk of a point of no return increasingly real. Much like with climate change, the window to act is closing fast – and without coordinated global leadership, cleanup may come too late.